- Home

- Joel C. Rosenberg

Without Warning Page 18

Without Warning Read online

Page 18

“Gentlemen, it’s an honor to be here,” Holbrooke replied. “I’m so sorry for your loss. On behalf of the president and me, I hope you’ll accept our sincerest condolences.”

“Thank you, sir, that’s very kind,” I said. “I don’t believe you’ve ever met my brother, Matt.”

“No, can’t say I have had the pleasure—good to meet you, son,” the VP said, turning to shake Matt’s hand. “I can’t pretend to understand the pain you’re both going through. But I want you to know how much the president and I—and the nation—respect you both and how committed we are to bringing those responsible to justice.”

I stiffened—not visibly, I hoped. I wasn’t looking for a fight. Not here. Not now. I just wanted to make it through the day and help Matt do the same. But to hear the second most powerful man in the world lie to my face—on the grounds of a church, no less—was almost more than I could bear. Neither Holbrooke nor the president was serious about tracking down and terminating the emir of the Islamic State.

Why not just admit it? I thought. Why not just walk into the press center down the street, gather a bunch of reporters around, look into the cameras, and say to the American people, “Look, the president and I feel really bad about all the terrorism that Abu Khalif and ISIS have unleashed over the past days, months, and years. We didn’t see the attack on the peace summit in Amman coming. We didn’t pay attention to the warnings about the coming attacks on the Capitol or the rest of the country, much less on this little fishing village on the coast of Maine. Sure, we feel bad for the Collins family—and for all who have suffered at the hands of Radical Islam. And sure, we’re comfortable lying and telling you we’re winning, that we’ll never rest until we make Abu Khalif pay. But the truth is we’ve got better things to do than be obsessed with Abu Khalif. Dealing with the Middle East isn’t why we ran for office, and frankly we’re getting tired of thinking and talking about it constantly. There are much bigger priorities to deal with here at home than wasting so much time and money on events half a world away. So we’re cutting our Sunni Arab allies loose. We’ve offered the Jordanians barely any financial assistance to rebuild their capital. We’re not providing the Egyptians enough helicopters or drones or night-vision goggles or other state-of-the-art equipment to hunt down ISIS leaders. Neither of us attended the funeral of the Israeli prime minister. We’re slashing the American defense budget. We’re demoralizing our armed forces and intelligence community. We’re forcing a whole lot of good, experienced, irreplaceable men and women out of the military at a time we need them most. And we really couldn’t care less. This is what we’re doing. And there’s nothing you can do to stop us.”

As far as I was concerned, that was the truth—and it made my blood boil.

But I held my tongue.

It wasn’t as much of a struggle for Matt. It’s not that he didn’t have strong views, but he was a genuinely nice person. He didn’t hold a grudge. He simply didn’t see the value in it. And for all his disagreements on policy, he really was grateful the vice president of the United States had traveled from Washington to attend a memorial service for his family members. So as we stood there in the parking lot, the snow swirling about our faces, he thanked Holbrooke with a sincerity that both impressed and eluded me.

At the encouragement of the Secret Service, we began walking up the freshly shoveled sidewalk and across a courtyard, Matt and Holbrooke taking the lead, me a few steps behind.

As we entered a side door, we were greeted by Pastor Jeremiah Brooks, my mom’s pastor, and the rector who officiated here at St. Saviour’s, a kindly silver-haired woman. She handed each of us a program, and then the bells started ringing. It was precisely ten o’clock. Everyone but us was in their seats. The service was set to begin.

49

Pastor Brooks led Matt and me out into the sanctuary, to the pew in the first row.

The vice president and his security detail followed right behind us.

The first people we saw were Annie’s parents and two younger sisters, all of whom had arrived in town just a short time earlier after visiting the hospital in Portland. They were sitting in the second row, dressed in black, right behind our assigned seats, and they were a picture of grief. The youngest, still in her teens, was sobbing. Matt handed her a handkerchief I suspected he’d planned to use himself. Annie’s mother was barely keeping it together. Her mascara was already smeared and the service hadn’t even started. Annie’s father, a onetime Anglican priest and now an Indiana farmer with a tanned, leathery face and thick, calloused hands, was doing his best to be the stoic comforter for his family, but he looked like he’d been run over by a truck. He gave Matt an awkward hug. This was not a man comfortable with any displays of affection, least of all in public.

When we were all seated, the rector stepped to the front. She welcomed everyone and then introduced Pastor Brooks.

Brooks, a lanky man in his sixties, looked somber as he stepped to the pulpit, opened his Bible, and organized his notes. “Thank you all for coming,” he began, taking his reading glasses off to look out over the crowd of nearly three hundred people. “We are gathered this morning to honor, remember, and celebrate the lives of Margaret Claire Collins and Joshua James Collins.”

The two caskets—one long, one short, each adorned with flowers—stood on metal supports at the front of the sanctuary. That put them about two yards away from us, and I found myself staring at the caskets as the pastor continued his opening remarks. Brooks explained that he had been my mother’s pastor for more than thirty years. He thanked Matt and me for asking him to officiate, and thanked the St. Saviour’s rector and staff for their hospitality. Finally he thanked the vice president for “honoring us with your presence.” Then he began his message.

I had no intention of listening. If I was going to come up with an alternative to the plan proposed by Agent Harris, now was the time to do it. Still, I was sitting in the front row, directly beside the vice president. I couldn’t exactly flip the program over and begin sketching out my plan. I had to at least look interested, and for me that posed a distinct challenge. Because I wasn’t.

To make matters worse, Brooks kept looking at Matt and me. Not the whole time, of course. He was addressing the entire congregation, but his gaze kept returning to us again and again, and it made me uncomfortable. After today, I couldn’t imagine I’d ever see this man again. I didn’t need him preaching to me. And yet he did.

“In the New Testament, the apostle Paul teaches us that ‘to be absent from the body’ is ‘to be present with the Lord,’” Brooks explained. “If you knew Maggie and Josh at all, you know that both of them had placed their simple trust in the shed blood of Jesus Christ on Calvary and that they are with him now and forever.”

His accent suggested southern New Hampshire roots, possibly even Boston, not Maine. It was vaguely reminiscent of how my grandfather used to talk.

“Both Maggie and Josh knew they were deeply loved by God. They truly believed the Word of God as recorded in the Bible: ‘I have loved you with an everlasting love; therefore I have drawn you with lovingkindness.’ They truly believed what the Lord said through the prophet Jeremiah: ‘I know the plans I have for you, plans for good and not for evil, plans to give you a future and a hope.’ What’s more, they both believed that Jesus was, in fact, the Messiah, the Savior, who fulfilled the messianic prophecies, who died on the cross, and who rose from the dead on the third day. I had the privilege of kneeling down and praying with Maggie the day she received Christ as her Savior and Lord by faith, the day she was forgiven of her sins and born again by the Holy Spirit. And almost three decades later, I had the great joy and honor of praying with Josh as he, too, decided to give his life to Christ. I know what they prayed, and I know how their lives changed as a result. That is why I can say with absolute certainty that they both knew the blessed hope of the gospel message.”

Again Brooks looked at Matt and me. I looked away.

“Now, there are many

things I loved and admired about Maggie Collins. But perhaps at the top of the list was that she was a faithful member of our choir. She was there every Sunday morning, rain or shine, and she sang with all her heart. She sang not for me or the congregation but to her Savior. You could hear it in her beautiful voice. You could see it in her lovely, sparkling eyes. She didn’t just believe she was going to heaven when she died—she knew it. She believed Christ’s promise, ‘I am the resurrection and the life; he who believes in Me will live even if he dies.’ She believed his words to the repentant thief on the cross that ‘today you will be with Me in Paradise.’ Without a shadow of any doubt at all, she absolutely knew that when she breathed her last breath here on earth, she would take her first breath in heaven in the very presence of her God and Redeemer forever and ever—and frankly, she couldn’t wait.”

Memories of my mom singing in the choir came flooding back. And she didn’t just sing in church. I suddenly found myself remembering her singing or humming old hymns of the faith all the time—while she was cooking, while she was cleaning, while she was driving to the supermarket. The woman simply wouldn’t stop. It used to drive me crazy. But what I wouldn’t give now to hear her hum “It Is Well with My Soul” one more time.

“And little Josh—oh, what a heart for Jesus,” the pastor continued. “He would come up to Bar Harbor in the summers to visit his grandmother, and he would participate in our vacation Bible school, and he was such a joy. Two summers ago Josh memorized sixty-two Bible verses in six weeks. Sixty-two! His favorite was not exactly one you’d expect for a young boy. It was John 15:13—the words of our Savior: ‘Greater love has no one than this, that one lay down his life for his friends.’ Now, I have to say, I’ve been pastoring a long, long time, and I’ve met a whole lot of kids, but I never met anyone quite like Josh.”

The more the pastor spoke, the deeper my remorse became. I thought about how little I really knew Matt’s kids and how much I had missed in their lives. I’d never known Josh had memorized so much Scripture. Nor that he’d had a favorite verse. Nor what it was. And then it struck me that this was the very verse Khachigian had quoted in his letter to me.

“Last Thursday night, what looked like a tragedy to us was not a tragedy for Maggie and Josh,” the pastor continued. “The spirits of these beloved family members and friends were taken from us. But they are not lost. Oh no. Maggie and Josh are gone, but they are not dead. They are more alive today than they have ever been. These two saints are alive and well in the throne room of heaven. Right at this moment, Maggie and Josh are worshiping at the feet of the King of kings and the Lord of lords, our great God and Redeemer, Jesus Christ. Their race is finished. Their mission here on this earth is complete. They are home, safe and sound, awaiting us to join them, if we, too, are in Christ. But, my friends, your only hope of seeing them again is to give your soul to the God they entrusted their souls to, and to do it before you breathe your last here on earth.”

As I stared at those coffins, the finality of it all hit me hard. For the past several days, I’d been living on adrenaline, duty, and denial. But sitting there in that church, looking at those wooden boxes, the brutal, unfair, cruel reality finally came crashing down on me. Mom and Josh were gone. Forever. They were never coming back. And all the family events I’d missed, skipped, ignored—they were gone too, never to be recaptured.

“My friends, one day, whether we want to or not, whether we’re ready or not, you and I will stand before the judgment seat of Christ,” the pastor continued, his voice unexpectedly calm, his manner surprisingly gentle, not like the hellfire-and-brimstone preachers of my cynical imagination. “We’re all going to pay the piper. If you’re still an unforgiven sinner when you die, the Bible says you’ll be the one who pays for your own sins. That is, you’ll go to hell, forever, with no way of escape. But the Bible also says that if we repent and receive Christ, then he pays for our sins—in fact, he already did, when he died on the cross in Jerusalem two thousand years ago.

“So today you have a choice to make: say yes to Christ, receive him as your Savior—as Maggie and Josh did—and God promises in his Word to forgive you. He’ll adopt you as his child. And when you stand before him one day, you’ll stand there as one forgiven, not one condemned, and he will welcome you into his open arms—just as he so eagerly and lovingly welcomed Maggie and Josh on Thursday night. Or say no, and roll the dice. It’s your choice. But I beseech you as a man of the cloth: don’t gamble with your eternal future.”

I shifted uncomfortably in the pew. As much as I wanted to resent the pastor and all he was saying, I couldn’t. He was speaking to me, and he was connecting. I was trying not to listen, but I simply couldn’t help it.

When the pastor finished, we sang a hymn, and then it was my turn to speak. I had a pit in my stomach as I stared out at the congregation through tear-filled eyes, feeling racked with guilt so overwhelming I could barely breathe. In pursuit of my dream of being an award-winning foreign correspondent like my grandfather, I had essentially abandoned my family. I hadn’t been there when they’d needed me. I hadn’t been there for the big moments in their lives. And now, because of me, two of them were dead, and two others were lying in an intensive care unit, fighting for their lives.

The truth is, I don’t remember what I said for the next few minutes. I hope I thanked the pastor for his beautiful words. I hope I said some nice things about Mom and about Josh. I honestly cannot recall a single word that came out of my mouth. It couldn’t have been too bad. I do remember people coming up to me after the service, in the receiving line, thanking me for honoring my family so beautifully.

But I’ll never forget what the vice president said after me because it so infuriated me. Holbrooke dutifully expressed his and the president’s condolences to Matt and me and to our family and assembled friends. Somebody had fed him a few details about my mom and Josh—even some tidbits about Annie and Katie—that he sprinkled throughout his prepared remarks as though he’d known them personally, as though he’d been an old friend. That didn’t bother me. Nor did it bother me—too much, anyway—that he was using the administration’s boilerplate language about “the scourge of violent extremism,” and about the “cowardly attacks of those who claim to speak in the name of Islam but have no idea what this great religion of peace is truly all about.” What did bother me—what absolutely enraged me—was something he said almost in passing toward the close of his remarks.

“As we lay to rest these two heroes—not victims, but true American heroes—let there be no doubt: We are winning the war against ISIL. We have liberated Mosul. We have liberated northern Iraq. We are killing their leaders. We have them on the run. What we have seen this past week is tragic, but rest assured, these are among the last violent spasms of a cruel but vanquished movement.”

The last violent spasms? A cruel but vanquished movement?

What planet was he living on? Nearly twice as many Americans had just died at the hands of the Islamic State as had on 9/11. Nearly as many Americans had perished in one week at the hands of Abu Khalif as in ten years of fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq. ISIS was hardly “vanquished.” It might have lost its grip on northern Iraq, but it was solidifying its grip elsewhere. It was expanding its caliphate into Yemen, Somalia, and Libya. It was recruiting tens of thousands of new foreign fighters and raising millions of dollars for its jihad against the West. Yet this administration couldn’t or wouldn’t see it. They simply refused to throw their full might into crushing this evil force once and for all.

At that moment, something in me snapped. I was suddenly consumed by a toxic and rapidly intensifying feeling of humiliation, compounded by guilt and fused with rage. By the time the service was over, I was seething. Something had to be done. Abu Khalif was engaged in nothing less than genocide. He had to be stopped. Who was going to do it? The president? The vice president? Not a chance. They were abject failures, and nothing about that was going to change. The world couldn’t wait for a new ad

ministration and a new plan. Neither could I. Neither could what was left of my family. That much was clear, and that certain knowledge left me with no other choice and not a shred of doubt.

I knew what I had to do, and I now had a plan.

50

TEL AVIV, ISRAEL

A brutal winter thunderstorm was bearing down on Israel’s largest coastal city.

I sat in the Royal Executive Lounge on the fourteenth floor of the Carlton Hotel, a few blocks north of the U.S. Embassy, nursing a Perrier as I watched the driving Mediterranean rains pelt the windows. Outside, palm trees bent in the forty-mile-per-hour winds. Streaks of jagged lightning illuminated the dark sky, and crashes of thunder rocked the building.

My pocket watch said it was five o’clock. I’d come to the same place, sat in the same leather chair, looked out the same window for the fourth day in a row. My contact had yet to show up. Maybe this was a complete waste of time. But I didn’t see any other way. So I sat, and I waited, and I tried to be patient. Not exactly my strong suit.

What bothered me most was that I’d nearly blown up my newly mended relationship with my brother to get here. Matt was furious with me. And I certainly understood why he felt betrayed.

Initially he’d liked my plan, but that’s only because I hadn’t told him all of it.

The part I told him about when we were alone in the rector’s office after the memorial service had been straightforward enough. We would accept Harris’s proposal to put us into the Witness Security Program, but with one caveat: the FBI couldn’t kill us off.

We would agree to disappear from our daily lives for several months, perhaps even a year or more, until Abu Khalif was arrested and my testimony was needed or until Khalif was dead and my family and I were no longer in danger. I’d take an indefinite leave of absence from the Times. Matt would take an indefinite leave of absence from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. With the bureau’s help, we would slip away unnoticed, undetected, and undetectable. Harris would provide us with new identities, complete with driver’s licenses and passports and credit cards and mobile phones. We’d have fake names. We’d live by the aliases Harris provided. We would live, in other words, like anyone else in the Witness Security Program, with one difference. We would not be “dead.” There would be no car bomb. There would be no funeral. The world wouldn’t think we were dead. They would just think we’d gone away to recover from the attacks and get the physical and psychological and spiritual help we so obviously needed. When we were better, we would come back.

The Copper Scroll

The Copper Scroll The Auschwitz Escape

The Auschwitz Escape The Last Jihad

The Last Jihad Damascus Countdown

Damascus Countdown The Persian Gamble

The Persian Gamble The Jerusalem Assassin

The Jerusalem Assassin Dead Heat

Dead Heat Israel at War: Inside the Nuclear Showdown With Iran

Israel at War: Inside the Nuclear Showdown With Iran The Last Days

The Last Days The Twelfth Imam

The Twelfth Imam Epicenter 2.0

Epicenter 2.0 The Kremlin Conspiracy

The Kremlin Conspiracy Implosion: Can America Recover From Its Economic and Spiritual Challenges in Time?

Implosion: Can America Recover From Its Economic and Spiritual Challenges in Time? The Third Target: A J. B. Collins Novel

The Third Target: A J. B. Collins Novel The Tehran Initiative

The Tehran Initiative Inside the Revolution

Inside the Revolution Implosion

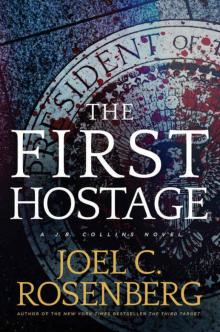

Implosion The First Hostage: A J. B. Collins Novel

The First Hostage: A J. B. Collins Novel